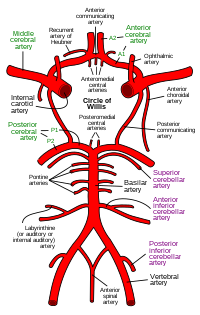

Arterial Circle of Willis

UPDATED: The arterial "circle of Willis" is a roundabout of arteries found at the base of the brain, allowing for collateral circulation at this level. This arterial circle has been described by many anatomists, but it was Thomas Willis (1621 - 1675) who described it in most detail, and he was the first to understand its function.

The circle of Willis receives blood from the two main paired arteries that provide blood supply to the head and brain: the carotid arteries anteriorly, and the vertebral arteries posteriorly.

This arterial circle is formed by the anastomosis of several arteries, paired and unpaired:

• Anterior cerebral arteries: These paired arteries are one of the terminal branches of the internal carotid arteries. They provide blood supply to the medial aspect and part of the lateral aspect of frontal and parietal lobes of the brain

• Anterior communicating artery: A single unpaired small artery communicating both anterior cerebral arteries and providing potential collateral circulation between them

• Internal carotid arteries: These two bilateral arteries are one of the branches of the carotid artery found at the root of the neck. Its two main terminal branches are the anterior cerebral arteries and the middle cerebral arteries.

• Posterior cerebral arteries: These two arteries are formed by the bifurcation of the basilar artery, which itself is formed by the junction of the right and left vertebral arteries. The posterior cerebral arteries provide blood supply to the occipital lobe and part of the temporal lobe of the brain

• Posterior communicating arteries: These paired arteries provide communication between the carotid and vertebral arterial territories

• Middle cerebral arteries: Although not technically part of the arterial circle of Willis, these paired arteries are one of the two terminal branches of the internal carotid arteries. The middle cerebral artery travels deep in the lateral sulcus (Sylvian fissure) of the brain and provides blood supply to the lateral aspect of the brain including the frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, and insular lobes

The arterial circle of Willis provides all of the arterial blood to the brain. Cerebral blood flow in humans averages 55 mL per 100 g of brain tissue per minute. This is a about over 742.5 mL/min for the average 1350 g brain. Depending on the situation the brain will use between 15 to 20 percent of the total cardiac output, although by weight the brain is only about two to three percent of the average body weight. Incredibly, the brain uses more oxygen that most organs averaging close to 25% of the total oxygen needs of the body!

The importance of the arterial circle of Willis is that beyond this point the arterial supply to the brain becomes terminal, that is, there are little or no anastomoses between the bifurcating branches exposing the brain to ischemia and necrosis should there be an arterial stenosis or stricture. The circle of Willis is an area prone to aneurysms, with over 27,000 cases yearly in the US.

For an image of the vascular territories of the brain, click here.

Thanks to Jackie Miranda-Klein for making me review this post and update it!... and congratulations to Jackie for starting her Physician Assistant Master's degree at Kettering College. Dr. Miranda.

Image in the Public Domain. Courtesy of www.wikipedia.org

Clinical anatomy, pathology, and surgery of the brain and spinal cord are some of the lecture topics developed and delivered by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc.