This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Letter from Ephraim McDowell

to Robert Thompson

As some of you may know by now, I am a collector of antique medical books and books that relate to the history of anatomy and medicine.

As important as the books themselves are, there are details beyond the book itself that can take hours of my time doing research. The first one is the bookplates (also known as Ex-Libris). The have been used for centuries by book owners and collectors to identify the books in their collections, a tradition that seems to be falling in disuse. Not me, I have one that you can see here. Some of these can lead to places that you cannot imagine initially. One of these bookplates took me to research a potential resident ghost in a library!

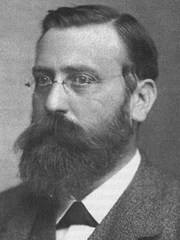

Provenance is also important. Where was it printed? Who owned it? Who was the illustrator? etc. I recently acquired a second copy of the book “EPHRAIM MCDOWELL, FATHER OF OVARIOTOMY AND FOUNDER OF ABDOMINAL SURGERY. With an Appendix on JANE TODD CRAWFORD”. By AUGUST SCHACHNER, M.D. Cloth, 8vo.A p. 33I. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott CO., I921. Dr. McDowell has also been featured in this blog in the series "A Moment in History".

This second copy is most valuable because of the papers found within the book. There is a series of notes, newspaper clippings, and copies of letters! Here is a detail of what I have found:

The book seems to have belonged to Cecil Stryker, MD.,a physician in Cincinnati, and one of the founders of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). There is a copy of a letter by Dr. Ephraim McDowell to Dr. Robert Thompson (Sr.) dated January 2nd, 1829, a year before Dr. McDowell's death. The letter is shown in the image attached. In this letter Dr. McDowell describes in his own words the ovariotomy he performed on Jane Todd. He also describes other ovariotomies he performed and his opinion on "peritoneal inflammation".

There is a note from Dr. Cecil Striker to "Bob" dated 6/3/73 when he gifted a copy of this book. In the note Dr. Striker explains that he bought several copies of the book and he is sending this copy to him. There is also a copy of Dr. McDowell's prayer (costs 25 cents), and a page of the Kentucky Advocate newspaper published in Danville, KY and dated Sunday April 15, 1973 on the restoration of Dr. Alban Goldsmith home, a surgeon who assisted Dr. McDowell in his first ovariotomy (first in the world, that is).

Last, there is a note dated September 16, 1974 from the wife of Dr. West T. Hill, Chairman of the Dramatic Arts Department at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. In this handwritten note she mentions the McDowell family reunion that took place on June 15 and 16, 1974 in Danville. With the note comes the program and registration form for the festivities! Dr. West T. Hill was one of the many responsible for the restoration of the MacDowell Home and Museum. Today Danville has the West T. Hill community theatre that honors his name.

All of this in one book, as I always say "You know where you are going to start reading it, but you never know where are you going to end in researching it". This book will be a great addition to my library catalog. Dr. Miranda.