| For the first segment of this article, click here.

...continued...

We believe the arguments in favour of scurvy unfortunately are not sufficient to draw a conclusion. And for each of the argument in favour of the scurvy theory, there are strong counterarguments too.

We will examine the main arguments here

1. Travelers to the Holy Land did have not enough food to eat that contained vitamin C.

There is no evidence that Vesalius, a man of means with introduction letters from the King of Spain, was deprived of food during his travels in the Holy Land. He could certainly buy food, and probably stayed at monasteries, sharing the same food that protected the residing monks from developing scurvy. And while scurvy was not uncommon, residents did not die in large numbers because of lack of vitamin C. Dying from scurvy was, even then, was limited to a small segment of the population.

Minimal daily intake of vitamin C for an adult is 90 mg per day [aa]. Most of that intake comes from fruits and vegetables (oranges, grapefruits …) but liver and kidney are also sources of vitamin C. These are all foods that Vesalius would have consumed in Jerusalem.

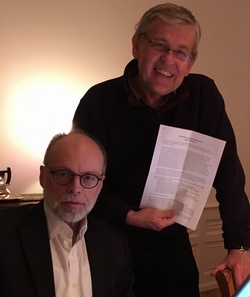

|

Dr. Rudi Coninx, and Theo Dirix, authors of this article

|

| 2. The long sea voyage led to scurvy.

The sea voyage is too short (40 days) to develop scurvy. It takes about three months (120 days) for scurvy to develop [8]. In one study it took healthy volunteers four months to develop signs of scurvy when fed a vitamin C deprived diet [9] although some showed signs at day 29. The first sign to appear was petechial haemorrhage. In 1939, Johan Crandon, a surgical resident at Boston City Hospital, experimented on himself by eating a diet totally devoid of vitamin C [x]. Fatigue developed after 3 to 4 months, and the pathognomonic hyperkeratotic papules appeared on day 134 and the perifollicular haemorrhages on the legs on day 162. Symptoms appear after 3 to 4 months only, and there is no evidence of this in any description of Vesalius symptoms.

It has also been argued that the trip through the Sinai desert must have contributed to the presumed low intake of vitamin C.

Vesalius’s entire stay in the Holy Land, including the Sinai desert trip –presumably lasting a month and a half- did not last for more than 4 months: he arrived in Jerusalem in May 1564 and boarded ship in Alexandria in September 1564. We believe this is not long enough to deplete all vitamin C and cause symptoms, even adding a 40 day sea voyage. And it is unlikely that his stay in Jerusalem was entirely free of vitamin C, as he was a respected guest of high authorities. We know that there was “no hint of shortages before their departure from Egypt” [Plessas]

Most studies indicate the earliest detectable change occurs after 120 to 180 days [xx] although there are studies where early signs appear earlier [xxx]. But in this study, which was stopped after 3 months, no serious effects occurred.

3. “Clinical description is typical for scurvy”.

This is simply not true. The clinical description we have, from second hand accounts, are vague and non-specific. The clinical signs and symptoms of scurvy are well known and clearly described today [10]. The typical clinical signs for scurvy are absent from all accounts: gingival bleeding, an early and typical sign, or the “rotten mound” is never mentioned. Subcutaneous bleeding [11] – ecchymoses - or joint pains, leading to difficulties walking, are never mentioned. Gum bleeding are typical signs, and so are swollen and painful legs, also leading to difficulties in walking [12]. They are all absent from the accounts. Non-specific signs such as laziness are also typical, with muscle pain in the legs as an initial sign, but they always evolve into bleeding, gum problems, putrid smell and other signs that Vesalius would have described. As a doctor, Vesalius would have been well placed to recognize these signs and to describe them. None of them appear in any account.

Authors claiming typical signs were present make a lot of the so-called melancholy and refer to the writings of the 16th century expert Johannus Echthius who wrote a treatise about scurvy in Latin, as was customary in these days, in 1541, although it was only published after his death in 1556 [13] Despite being considered an expert on scurvy, Echtihius –and all “experts” of his day could recognize the disease – they knew little about the causes of scurvy, its link with vitamin C and the treatment. In fact Echthius and his 16th century colleagues were dead wrong about the causes of scurvy. Echthius obtained his knowledge entirely from studying Greek and Roman classics, Celsus, Galen and others, and came to the conclusion that scurvy was caused by a blocked spleen, leading to an excess of black bile. The treatment therefore consisted in hot and wet medicines like oil and vitriol. The only useful cure, citrus juice, was considered a “cold” medicine, therefore of no use [14]. Doctors at the time recommended avoiding fruits and vegetables in case of scurvy! Knowledge about the causes of scurvy would have to wait till the work of James Lind, an officer of the British Royal Navy who published his now famous treatise on scurvy in 1753 [15]

But Echthius did know how to recognize the symptoms of scurvy: stomachache, a complaint of the mouth, and sceletyrbe, a complaint of the legs. Vesalius showed none of these symptoms.

In another argument in favour of the scurvy theory, it is claimed that extreme fear and irrational behaviour … are well known early symptoms [Plessas ]. This is not the case. Lind was correct when he observed that “a listlessness to action … a lazy inactive disposition” that degenerates in “a universal lassitude” [Hisrchman] are typical signs. This is also the observation of one of the authors (RC) having observed scurvy patients in Ethiopian prisons [xx]

|

Article continued here: Did Andreas Vesalius really die from scurvy? (3)

Sources:

1. https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2014/10/15/the-death-of-andreas-vesalius/ accessed 27.12.2016

2. Matheson Cullen, G. Vesalius and the inquisition myth. Lancet, January 14, 1928, p 105-6.

3. Dirix Th. In search of Andreas Vesalius. The quest for the lost grave. Lannoo, 2014.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Vesalius accessed on January 21, 2016

5. Biesbrouck M, Goddeeris Th, Steeno O. The last months of Andreas Vesalius. A coda. In Vesalius, Acta Internationalia Historiae Medicinae. 2012, 18 (No 2), 70-75.

6. Plessas P. http://www.parathemata.com/2014/09/pavlos-plessas-powerful-indications.html 2014. Accessed January 21, 2016.

7. http://www.clinicalanatomy.com/andreas-vesalius

Aa https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/

8. Fain, O. La Revue de Médecine Interne, 2004; vol 25, Issue 12, 872-880.

9. Hodges RE, Hood J, Canham HE, Sauberlich HE, Baker EM. Clinical manifestations of ascorbic acid deficiency in man. Am J Clin Nutr 1971;24:432-43.

x. Hirschman JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 1999, 41; No 6, 895-909.

xx. Bartley W, Krebs HA, O’Brien JRP. Vitamin C requirement of human adults. Medical Research Council Special Report Series No 280. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; 1953. P 1-179. Quoted in Hirschmann et al.

xxx Hodges RE, Baker EM, Hood J, Saueberlich HE, March SC. Experimental scurvy in man. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1969;22:535-48.

10. Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 1998; p 484-85

11. Leung FW, Guze PA: Adult scurvy. Annals of Emergency medicine; 1981; 10:652-655

12. Bennet M, Coninx R. The mystery of the wooden leg: vitamin C deficiency in East African prisons. Tropical Doctor, 2005; 35: 81-84.

13. Carpenter K. The history if scurvy and vitamin C.Cambridge University Press 1986, p29.

11. Bown S R. 4he Age of Scurvy. How a surgeon, a mariner and a gentleman helped Britain win the battle of Trafalgar. Summersdale, 2003, p 96-99.

15. Lind J. A treatise of the scurvy. Containing an inquiry into the nature, causes and cure of that disease. Together with a critical and chronological view of what has been published on the subject. Edinburgh: Sands, Murray and Cochran: 1753.

16. Kinsman RA, Hood J: Some behavioural effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1971, 455-464.

17. Biesbrouck M, Goddeeris Th, Steeno O: ‘Post Mortem’ Andreae Vesalii (1514 – 1564). Deel II. Het graf van Andreas Vesalius op Zakynthos. A. Vesalius, nr.4 December 2015. [in Dutch].

18. Bruce M Rothschild. Scurvy imaging. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/413463-overview

|