Resumen

Esta revisión apunta a dar luz sobre un problema evidente entre docentes de Anatomía Humana, profesionales y docentes clínicos, la existencia de términos anatómicos inexactos, complejos o inespecíficos, además de la existencia de Epónimos y Sinonimia, problema del cual los más perjudicados son los alumnos de pregrado en sus procesos formativos iniciales. Se darán definiciones semánticas y se situará dentro de un contexto histórico la adquisición de nuevas nomenclaturas y terminologías Anatómicas, buscando con esto justificación a la actual “Terminología Anatómica” la cual tiene por objetivo el desplazar la antigua “Nomina Anatómica”.

En la parte final se entregarán ejemplos característicos de términos anatómicos, enfrentando el término antiguo con el que sugiere la actual terminología anatómica. (Back to top)

Palabras Claves: Terminología Anatómica, Nomenclatura Anatómica, Epónimos

Introducción

La anatomía es la ciencia que se preocupa de estudiar la forma, conformación y las interrelaciones de todas las estructuras corporales. Al estudiarla sentamos las bases para la compresión de un individuo bajo un concepto de normalidad. De aquí la gran importancia de la disciplina, ya que posteriormente con esta importante base de conocimiento se puede comprender y tratar la anormalidad.

Un fenómeno frecuente que subyace a todo tipo de lenguaje es la existencia de varios términos para designar un mismo concepto (sinonimia) y además de la posibilidad de que un mismo término pueda poseer varios significados (polisemia) (1). En el lenguaje científico y médico esto es común, con mayor razón en las ciencias morfológicas y de ellas, la anatomía es particularmente la que en términos prácticos genera la mayor cantidad de controversias y desencuentros, ya que los términos usados en clínica, en referencia a estructuras corporales tienen su origen en la terminología anatómica y son de uso diario.

A la gran cantidad de términos anatómicos existentes se suma las confusiones generadas cuando en algunos países y en otras ocasiones, traductores de escritos anatómicos, le asignan un nombre diferente a cada estructura o elemento. Esto lleva a escuchar habituales quejas de profesionales y alumnos frente a “un término” expresado de diferentes formas, ya sea, por los diferentes profesores de anatomía o por los docentes y ayudantes en el pabellón y laboratorio anatómico. Particularmente, en nuestro medio, esta situación es una constante, ya que debemos responder a dialécticas regionales e internacionales, producto de la literatura que recibimos desde el extranjero.

Con los años esto ha generado un conflicto en el desarrollo científico y divulgación de las ciencias morfológicas, separando progresivamente a los docentes de anatomía con los profesionales clínicos. (14)

En el transcurso de esta revisión se darán definiciones semánticas y se situará dentro del contexto histórico la adquisición de diversas nomenclaturas y terminologías, hasta llegar al último gran esfuerzo por consensuar los términos anatómicos, la “Terminología Anatómica” la cual en la actualidad ha desplazado a la anteriormente llamada “Nómina Anatómica”.

En la última parte se hará referencia a términos de uso habitual, fundamentalmente del aparato musculoesquelético, de mayor uso en el quehacer kinésico, enfrentando el termino antiguo con el que sugiere la actualizada terminología anatómica.

(Back to top)

Terminología y Nomenclatura

La palabra terminología puede entenderse de diferentes maneras: en primer lugar, la terminología es el conjunto de vocabulario especial de una disciplina o un ámbito de conocimiento; en segundo lugar, la terminología puede entenderse como una disciplina, que tiene por objeto la construcción de una teoría de los términos, el estudio de los mismos, su recopilación y sistematización en glosarios especializados como las nomenclaturas. (2-5) (12) (16).

El problema terminológico no es nuevo para anatomía, han transcurrido más de 100 años desde que se inició un proceso que busca la unificación de criterios a nivel internacional (6), que consiste en priorizar un término sobre el resto de los equivalentes, mediante la elección de un término único, como el aceptable para designar un solo concepto, rechazando con esto los anteriores sinónimos. (7)

Con este objetivo surgen las nomenclaturas que son un tipo de terminología aplicada a cosas naturales u objetos que forman series más o menos homogéneas cuyas denominaciones se crean conforme a reglas uniformes. Se crean con el objetivo de reducir al máximo la diversidad terminológica, escogiendo el término que posea mayor fuerza descriptiva, mayor simplicidad y especificidad. (1, 2, 5)

La construcción de estas nomenclaturas médicas, así como de listas de términos y glosarios normativos (aprobados por autoridades científicas oficiales), que aspiran a lograr la uniformidad terminológica en la denominación de conceptos, parten de la idea que la variación es un perjuicio para la comunicación y de que es imprescindible establecer una terminología única y aceptable para todos los sectores implicados en la comunicación médica, como docentes, investigadores, redactores, traductores, correctores, editores, bibliotecarios y otros. (1, 2,8,9)

Autores, como A. Manuila y diversos expertos de la OMS, consideran que la diversidad deja sumida a la terminología en un estado de “confusión” tal, que se convierte en un obstáculo para el propio “progreso” de la ciencia. Hacen referencia estos autores que un término como mielofibrosis tiene 12 sinónimos en inglés, y el correspondiente en alemán posee 13, y en francés existen 31 términos equivalentes del mismo. Esta situación es calificada por dicho especialista como de “desorden”, en la medida en que es un obstáculo para la comparabilidad de los datos y el almacenamiento y recuperación de la información médica. (9,10).

(Back to top)

Antecedentes Históricos

La evolución sufrida por el lenguaje anatómico es el fiel reflejo de la experiencia histórica de los pueblos y de su desarrollo cultural. Sus cambios semánticos y ortográficos, metáforas, mezclas lingüísticas, conflictos nacionalistas y personalistas por la primacía en las denominaciones, impropiedades léxicas, paronimias y sinonimias, expresan esta rica diversidad. (8).

Es casi imposible sustraerse de estos puntos. Felipe Mellizo expresa en “Literatura y enfermedad”: El profesor de anatomía nombraba en latín las partes, intrigantes, magníficas, del cuerpo, y eso permitía, eso permite, que todos comprendamos que allí no es sólo anatomía lo que se explica, sino que se está explicando también la historia de la cultura. (8,11)

Como es sabido, durante la Antigüedad y la Baja Edad Media, la lengua de la Anatomía, como de toda la ciencia, era el griego, y en menor medida el latín. A partir del siglo XI, la presencia de los árabes en Europa llevó a la realización de traducciones y adaptaciones al latín de textos árabes que contenían el lenguaje clásico (latín). El desconocimiento de terminología latina obligo a introducir por parte de los traductores, términos árabes. Con la llegada del Renacimiento se llevo a cabo una restitución de los textos griegos y latinos originales, recuperando la terminología (6).

Los descubrimientos anatómicos posteriores, con bases más sujetas a la experimentación y la observación directa, traen como consecuencia la aparición de neologismos, no siempre bien construidos, además de numerosos epónimos (dar nombre a una estructura con el apellido o nombre del descubridor) con las consiguientes pugnas en la autoría de los hallazgos anatómicos. (8)

En este aspecto es sorprendente la riqueza metafórica del léxico anatómico y con una semánticas apegada a la realidad humana y a la vida cotidiana: acetabulum designaba un recipiente para contener vinagre; alveolus viene del latín alveus ‘colmena’; amígdala procede del griego Amygdala ‘almendra’; clítoris era para los griegos una colina o pequeño promontorio; gínglimo procede del griego ginglymós ‘gozne’. Inclusive hay metáforas vegetales, animales, geográficas o domésticas que revelan esta tendencia tan humana expresada en el léxico anatómico, estructuras como “deltoides”, “bipenado”, unipenado” dentro de muchas más. (8).

(Back to top)

Nomenclaturas Anatómicas

Los primeros análisis con respecto a la terminología se inician en 1887 en Leipzig, Alemania, continuándose en el Reino Unido en 1894. Producto de esto y después de siglos de acumulación de términos anatómicos se junta un grupo de anatomistas alemanes (el líder fue Wilhelm His) en Basilea en 1895 dando fruto a la primera Nomenclatura Anatómica Internacional con el nombre de Nomina Anatómica; en inglés suelen referirse a ella como Basle Nomina Anatomica o BNA (Nomenclatura Anatómica [Internacional] de Basilea)(6). Fundamentalmente trata de eliminar diferencias nacionales, en forma honorífica mantiene el nombre de uno o más científicos que hubiesen sido los primeros en describir una estructura. En la práctica, sólo se impuso entre los profesionales de habla alemana y en gran parte de Norteamérica. (6).

Con anterioridad a la II Guerra Mundial, se publicaron de forma casi simultánea una revisión británica (The Birmingham Revision, BR, en 1933) y otra alemana (Jenaer Nomina Anatomica, JNA, en 1935) que vinieron a complicar más aún la situación. De ellas, la que alcanzó más importancia fue la alemana y conocida en inglés como Jena Nomina Anatomica o JNA. (6)

En el V Congreso Federativo Internacional de Anatomía que fue llevado a cabo en Oxford, Inglaterra, en 1950 y en un intento de uniformar la nomenclatura anatómica, la Federación Internacional de Asociaciones de Anatomistas (FIAA) creó un Comité Internacional de Nomenclatura Anatómica que elaboró una nueva nomenclatura latina internacional, aprobada en 1955 con motivo del VI Congreso Federativo Internacional de Anatomía, que se celebró en París, aparece la Parisiensia Nomina Anatomica o, en inglés, Paris Nomina Anatómica o PNA (Nomenclatura Anatómica [Internacional] de París). De hecho cuando se hace referencia en los textos anatómicos de final del siglo XX a la expresión Nomina Anatómica a secas, casi siempre hace referencia a esta Nomenclatura Anatómica de París. En los congresos mundiales anatómicos de Nueva York (1960), Wiesbaden (1965), Tokio (1975) y México (1980) se efectuaron revisiones y nuevas ediciones a la nómina. Lamentablemente las referencias para estas revisiones son muy confusas ya que por ejemplo tras el congreso de Tokio, algunos autores de lengua inglesa hablaban de Nomina Anatomica 4th edition (o Paris Nomina Anatomica 4th edition), mientras que otros preferían hablar de Tokyo Nomina Anatomica. Y eso sin tener en cuenta las comunes confusiones con nuevas ediciones de reimpresiones en los diferentes países. Una disputa en 1985 entre la FIAA y el Comité Internacional de Nomenclatura Anatómica terminó con la ruptura de relaciones entre ambos organismos en 1989, cuando el Comité publicó la sexta edición de los Nomina Anatómica sin someterla a la aprobación del XIII Congreso Federativo Internacional de Anatomía celebrado en Río de Janeiro. En agosto de 1989, la FIAA decidió crear un nuevo Comité Federal de Terminología Anatómica con el encargo de elaborar una nueva nomenclatura anatómica internacional. En Lisboa 1994 se incorpora el idioma ingles como valido dentro de la terminología. Tras varias reuniones, el nuevo Comité publicó en 1998 la nueva Terminología Anatómica (Terminología Anatómica Internacional), que hoy ha sustituido a la Nomina Anatómica como nomenclatura anatómica oficial en todo el mundo. (6)

En la actualidad existe el Comité Internacional Mundial que revisa la Terminología en Histología y Embriología, además de la terminología Veterinaria.

(Back to top)

Términos

Con el interés de ejemplificar los cambios generados por la Terminología Anatómica, haremos referencia a términos de uso común en la jerga anatómica y clínica los cuales deberían según la terminología anatómica ser sustituidos:

Anatomía General

Partes del cuerpo

Extremidad superior cambiar por Miembro superior

Extremidad inferior cambiar por Miembro inferior

Cintura escapular cambiar por Cintura o Cíngulo Pectoral

Términos descriptivos

Borde externo cambiar por Borde o Margen lateral

Borde interno cambiar por Borde o Margen medial

Sistema esquelético

Apófisis cambiar por Proceso

Escotadura cambiar por Incisura

Maxilar superior cambiar por Maxila - Maxilar

Maxilar inferior cambiar por Mandíbula

Agujero cambiar por Agujero o Foramen

Omoplato cambiar por Escápula

Cubito cambiar por Úlna

Peroné cambiar por Fibula

Rotula cambiar por Patela

Astrágalo cambiar por Talo

Escafoides Tarsiano cambiar por Navicular

Articulación tipo Diartrosis cambiar por Art. Sinovial o Diartrosis

Articulación tipo Trocoide cambiar por Articulación Pivote

Articulación tipo Ginglimo cambiar por Articulación Bisagra

Articulación tipo Enartrosis cambiar por Art. Enartrosis o Esferoidea

Articulación tipo artrodias cambiar por Articulación plana

Músculos

Cubital Anterior cambiar por Flexor Ulnar del Carpo

1er Radial cambiar por Extensor Radial largo del Carpo

Supinador Largo cambiar por Braquiorradial

Extensor común de los dedos cambiar por Extensor de los dedos

Recto interno cambiar por Grácil

Epónimos

Órgano de Corti cambiar por Órgano espiral

Articulación de Chopart cambiar por Art. transversa del tarso

Ligamento de Bertin cambiar por Ligamento Iliofemoral

Fondo de Douglas cambiar por Excavación rectouterina o rectovesical

Nódulo de Aschoff-Tawara cambiar por Nodo atrioventricular

Nódulo de Keith-Flack cambiar por Nodo sinoatrial

Trompa de Falopio cambiar por Tuba uterina

Trompa de Eustaquio cambiar por Tuba auditiva

(Back to top)

Consideraciones Finales

Hay que estar consciente de que, en países como Francia y España, países de los cuales recibimos mucha bibliografía clínica la nomenclatura anatómica internacional no ha conseguido desplazar aún a la nomenclatura anatómica tradicional. Así, por ejemplo, el término internacional fibula para los españoles, sigue siendo ‘peroné’; El músculo Braquiorradial (musculus brachioradialis del latín) es ‘músculo supinador largo’; la arteria Carótida Común (arteria carotis communis) es ‘arteria carótida primitiva’; líquido cerebro espinal (liquor cerebrospinalis) es ‘líquido cefalorraquídeo’; Nervio fibular común (nervus fibularis communis) es ‘nervio ciático poplíteo externo’ y Linfonodos (nodus lymphaticus) es ‘ganglio linfático’. (8)

Es loable el esfuerzo que se hace a favor de una terminología universal, es el caso reciente de la cumbre de Terminología en el año 2002 en la que representantes de instituciones, organismos y redes de terminología de distinta índole, dieron fruto a la declaración de Bruselas, solicitando a los estados y organismos internacionales que en el marco de su política lingüística apoyen la creación de estructuras básicas de terminología, promuevan el desarrollo y la actualización de los recursos terminológicos, así como el acceso gratuito a las terminologías y en particular a aquella utilizada en los documentos oficiales de los gobiernos e instituciones internacionales. Si bien esto esta enfocado a políticas gubernamentales y de las tecnologías de la información se observa la tendencia actual a los consensos lingüísticos. En efecto, el conocimiento y empleo de las terminologías científicas tiene un impacto importante y creciente en el mundo globalizado, en el que las comunicaciones entre especialistas y usuarios procedentes de comunidades lingüísticas diversas se han vuelto una necesidad imperiosa. (13,15)

(Back to top)

Conclusiones

Así a 110 años de esfuerzo por unificar internacionalmente los términos usados en Anatomía exhortamos a alumnos, docentes y clínicos a usar la Terminología Anatómica, con lo que evitaríamos, ese estado de “confusión”, que se convierte en un obstáculo para el progreso de la ciencia.

El estudio de los procesos y antecedentes históricos nos aportan datos valiosos; una estructura habla de sí misma producto de su historia terminológica. Ortega y Gasset consideraban a las palabras como “algos humanos vivientes”, de ahí que afirmara que “cada palabra reclama una biografía”.

En una sociedad como la nuestra, que no siempre es capaz de reconocer que la investigación humanística exige el mismo rigor y profesionalidad que la investigación científica, hay que valorar los esfuerzos tendientes a consensuar las dos disciplinas y pensando siempre en el fortalecimiento de la Anatomía como ciencia fundamental y pilar del conocimiento de los profesionales de ciencias biomédicas.

(Back to top)

Bibliografía:

(1) Díaz Rojo, J. La terminología médica: diversidad, norma y uso. Panace. 2001; vol. 2 (4):40-48.

(2) Cabré, M. T. La terminología. Teoría, metodología y aplicaciones. Barcelona: Editorial Antárdia/Empúries; 1993.

(3) Cabré, M.T. Elementos para una teoría de la terminología: hacia un paradigma alternativo. El Lenguaraz Revista académica del Colegio de Traductores Públicos de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. 1998; vol 1 (1):59-78

(4) Cabré, M.T. Hacia una teoría comunicativa de la terminología: Aspectos metodológicos. La terminología representación y comunicación. Barcelona: IULA; 1999.p. 129-150

(5) Cabré, M.T. La terminología, una disciplina en evolución: pasado y algunos elementos de futuro. Debate Terminológico. 2008. Disponible en: www.riterm.net/revista/n_1/cabre.pdf

(6) FEDERATIVE COMMITTEE ON ANATOMICAL TERMINOLOGY. (FCAT). Terminología anatómica. Stuttgart, Georg Thieme Verlag; 1998.

(7) Wüster E. Introducción a la teoría de la terminología y a la lexicografía terminológica. Barcelona: IULA; 1998.

(8) Díaz Rojo, J., Juan José Barcia Goyanes (1901-2003), estudioso de la historia del lenguaje anatómico. Panace. 2003; Vol.4 , Nº (13–14).

(9) Manuila A. Progress in Medical Terminology. Basilea: Karger; 1981.

(10) Stewart WH. Towards uniformity in medical nomenclature. Statement by Surgeon General of the United States to WHO in May 1966. En: Manuila A. Progress in Medical Terminology. Basilea: Karger, 1981.

(11) Mellizo F., Literatura y enfermedad. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés; 1979.

(12) Temmerman, R. Towards new ways of terminology description: the socio-cognitive approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2000.

(13) Schnell B., Rodriguez N., La terminología: nuevas perspectivas y futuros horizontes. ACTA. 2008. Disponible en: www.acta.es

(14) Whitmore I. Terminologia Anatomica: new terminology for the new anatomist. Anat Rec (New Anat.) 1999; 257: 50-53.

(15) Rosse C, Terminologia Anatomica; Considered from the Perspective of Next-Generation Knowledge Sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14(2):120-33

(16) Weissenhofer, P. Conceptology in Terminology Theory, Semantics and Word Formation. Viena: TermNet.,1995.

(Back to top)

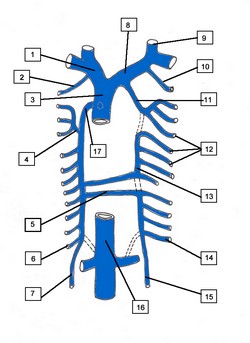

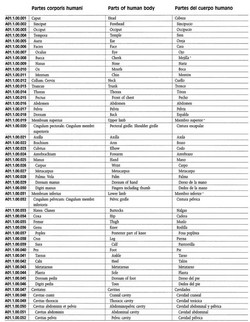

La imagen en este articulo es una página selecionada de la Terminologia Anatomica ilustrando la organización jerárquica que tiene el libro. Nótese la columna izquierda que indica el código de cada estructura.

Agradecimientos

Se agradece la exhaustiva revisión, comentarios y aportes del Profesor Dr. Alberto Rodríguez Torres, de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Chile.

Autores:

Cristián Uribe Vásquez

Kinesiólogo, Magíster en Ciencias Anatomía Humana

Docente, Universidad Andrés Bello – Chile

Rodolfo Sanzana Cuche

Kinesiólogo, Magíster Morfología Humana

Docente, Universidad de Chile

|