This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Book cover

As you know, I am interested in the history of Science, Medicine, and specially, Human Anatomy. Because of that and as part of this website we added a series called "A Moment in History". The objective was to create a series of articles to honor those individuals who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research including individuals who have contributed in different ways, but still added their life work to the advancement of medical knowledge.

One of the individuals who piqued my interest was Henry Gray, FRS author of one of the great teaching books on anatomy ever written, “Gray’s Anatomy”. This book was first published in England in 1858, later published in the USA from 1862 to 1990. The English Edition is still published and is now in its 42nd Edition.

I started to look deeper into his life which, I learned with surprise, was not only very short, but obscure. Researching into Henry Gray’s life, I came about this book: “The Anatomist – A True Story of Gray’s Anatomy” by William (Bill) Hayes.

Bill Hayes started looking into Henry Gray’s life with the intent of writing a biography. He rapidly run into a wall. Besides a well-detailed list of academic titles and positions, degrees awarded, and scientific papers that he published. As the author states “what I had gathered about him would amount to little more than a Curriculum Vitae”. So, he starts a journey to uncover more data about Gray’s life and his well-known book.

Part of his journey was to understand the importance of anatomy as a component of the medical curriculum. Bill Hayes was accepted as a participant in the anatomy laboratory for physical therapy students and later visited medical students in the anatomy lab. Just his observations and comments throughout the book on these activities is worth reading this book.

What is interesting is the lack of personal information on Henry Gray. To this date, we do not have information about his birth, either location or date. There is more information on his family that on the subject. Most agree that Henry Gray was born in 1827, but some propose 1825. Either way, there is no firm data. What we do know is that he died on June 12, 1861, having contracted smallpox most probably from his nephew Charles Gray. Henry Gray was 36 years old.

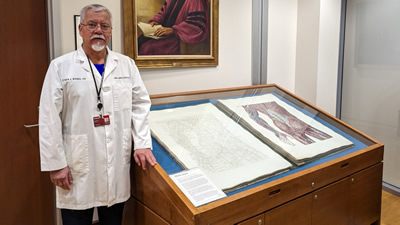

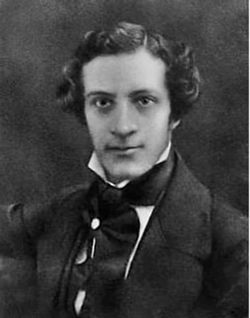

Gray and students

Here is one of the few photographs that exists of Henry Gray. In this particular 1870 picture by Joseph Langhorn, Gray is in the anatomy laboratory (forefront, third from the left) at St. George’s Hospital with his students. At the time it was customary for medical students to pose in the lab with bones and cadavers. This is a practice not in use today and disappeared circa 1930. For anyone interested in this now considered gruesome custom, I would recommend the book "Dissection" by John H. Warner and James M. Edmonson.

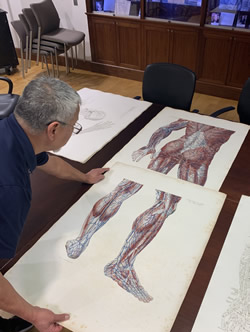

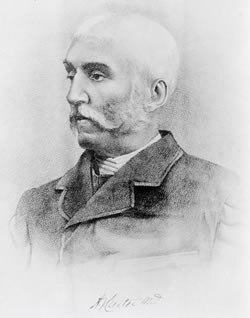

In his research, the author discovers Henry Gray’s collaborator and illustrator of the book: Henry Vandyke Carter, MD. Where Gray is obscure and with no personal information, Henry Carter writes a diary daily, and for some time he actually writes another diary that he calls “Reflections” on more personal and religious topics. Carter is a troubled, complicated individual blessed with incredible anatomical knowledge and drawing capabilities that can be seen throughout the book.

It is because of these diaries that we know Henry Carter and we can glimpse (almost at a distance) the character of Henry Gray, but it is not enough to elucidate his biography. In some ways it is like looking at an individual through a veil. You see him, but it is nebulous.

Much of the book is concentrated on Henry Carter, his life, his depression bouts, his self doubts and the work that he did illustrating Gray’s book. In some ways he is behind the scenes, and even though he did much of the dissection work and illustration, Henry Carter is mostly unknown to the anatomical world, as in may cases the medical illustrators are, with some notable exceptions.

Henry Carter is paid only 150 pounds for his work and even before getting paid he pays for a ticket to India where he accomplishes his objectives in life and in academia. Henry Carter eventually retires and comes back to England where he dies in 1897.

Bill Hayes and his partner visited rare book libraries at different universities and eventually go to London to visit areas and locations where Henry Gray lived and worked. There is a sense of accomplishment, but also a sense that we can almost touch the life of Henry Gray but fall short of seeing him.

The book ending is poignant, dealing with personal matters and thoughts on life and death. Eventually the author is very clear that the study of anatomy, although on dead subjects who donated their bodies to the universities is actually an activity that helps us understand life.

Bill Hayes is an awarded author of seven books, a frequent contributor to the New York Times and a photographer. More information about him and his activities at https://www.billhayes.com

Personal note: This is a book that I personally recommend and proud to add to my personal library. My one observation is that the author should have probably name the book “The Anatomists - A True Story of Gray’s Anatomy” as it is the story of the life of the two Henrys: Gray and Carter. In fact, I believe that Gray’s Anatomy could have been called “Gray’s and Carter’s Anatomy”, had history been slightly different – Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. “Henry Gray and Henry Vandyke Carter: Creators of a Famous Textbook" Roberts, S. J Med Biog 2000 8: 206-212

2. "Henry Gray, Anatomist: An Appreciation" Boland, F Am J Med Sci 1908 1827-1924

3. "The Anatomist: A True Story of Gray’s Anatomy" Hayes, B. Random House PG 2007